In the late 19th century, as the Belle Époque bloomed, a new art movement emerged from the streets of Paris, sweeping across Europe with its elegant, flowing lines and natural forms: Art Nouveau. [ read the full champagne story ]

Estimated reading time: 12 minutes

Alphonse Mucha and the Art Nouveau of Champagne

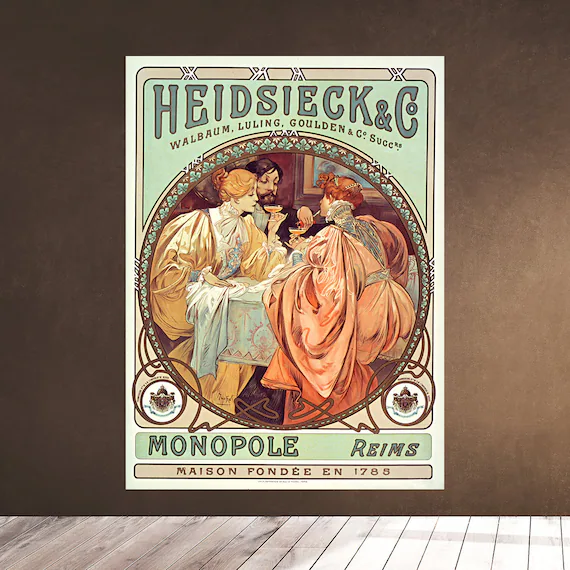

In the late 19th century, as the Belle Époque bloomed, a new art movement emerged from the streets of Paris, sweeping across Europe with its elegant, flowing lines and natural forms: Art Nouveau. At the heart of this revolution was the Czech artist Alphonse Mucha, a master of decorative art whose work transcended mere illustration to become a symbol of the era’s artistic and commercial innovation. Mucha’s genius was in transforming commercial advertising into high art, a skill perfectly showcased in his iconic posters for the world of Champagne.

Mucha’s signature style, characterized by a harmonious blend of idealized female figures, elaborate floral motifs, and intricate decorative patterns, became an instant sensation. His subjects, often draped in neoclassical gowns and adorned with halos of mosaic-like shapes, embodied a serene, almost spiritual beauty. This aesthetic, which he insisted was not merely “nouveau” but timeless, was a perfect match for the luxury and sophistication of Champagne.

His collaborations with major houses like Moët & Chandon and Champagne Ruinart are a testament to this synergy. For Moët & Chandon, Mucha created a series of now-famous posters for their “Dry Imperial,” “Cremant,” and “White Star” champagnes. These works feature his characteristic “Mucha women,” with flowing hair and soft, harmonious colors, often entwined with twisting vines and delicate flowers, perfectly capturing the effervescent spirit and elegance of the bubbly beverage.

The Mucha Foundation itself highlights his work for Moët & Chandon’s Dry Imperial in 1899, where he chose to depict a classical brunette adorned with ornate jewelry, visually representing the distinct taste of the Champagne. His poster for Champagne Ruinart in 1896 was equally impactful, included in the seminal Exposition d’Affiches Artistiques Françaises & Etrangères—a clear indication that his commercial work was celebrated on par with fine art.

Perrier-Jouët and the Spirit of Art Nouveau

While Mucha was a driving force behind the Art Nouveau poster, his influence is part of a broader story of how the art movement became inextricably linked with Champagne. This connection is perhaps best exemplified by the house of Perrier-Jouët and its iconic Belle Epoque Cuvée.

The story begins in 1902 when master glassmaker and one of the leading figures of the Nancy School of Art Nouveau, Emile Gallé, was commissioned by the Perrier family. Gallé designed a delicate, stylized motif of white Japanese anemones to be enameled directly onto four magnums. This beautiful design, with its sinuous, organic lines and floral elegance, perfectly embodied the delicate, floral essence of the Champagne itself. The design was so cherished by the family that it was stored away, only to be rediscovered in 1964 and chosen to adorn a new, prestige cuvée: the Perrier-Jouët Belle Epoque.

The legacy of this artistic partnership is preserved at the Maison Belle Epoque, the former family residence of the Perrier family in Épernay. The house, which now holds one of Europe’s largest private collections of French Art Nouveau, is a living museum dedicated to the movement. It features works by Gallé, Louis Majorelle, and Hector Guimard, showcasing the profound connection between the house’s identity and this artistic period. This fusion of art, nature, and craftsmanship highlights a shared philosophy—one where a dedication to beauty and meticulous detail is paramount, whether in crafting a vintage Champagne or designing a masterpiece.

The Art Nouveau style, whether through Mucha’s compelling posters or Gallé’s iconic anemones for Perrier-Jouët, did more than just advertise; it created a new visual language for luxury. It positioned Champagne as not just a beverage, but as an object of desire, a symbol of a golden era of art and life. For enthusiasts of both Champagne and art, the work of Alphonse Mucha and the heritage of Perrier-Jouët serve as a stunning reminder of a time when beauty flowed freely, from the tip of an artist’s brush to the bubbles in a flute.

An Ode to the Everyday: Alphonse Mucha, Art Nouveau, and the Soul of Champagne

For the discerning aficionado of both art and the world’s most luxurious sparkling wine, there exists a profound and intertwined narrative woven between the Belle Époque and the aesthetic philosophy that defined it: Art Nouveau. This story is not merely one of design but of a cultural movement that sought to re-enchant the everyday, to infuse beauty and meaning into the mundane, and to create a “total work of art” (Gesamtkunstwerk) where every object, from a building to a bottle of champagne, was a canvas for sublime expression. At the very heart of this artistic renaissance stand two figures who, though they never collaborated, represent the pinnacle of this union: the Czech master of the graphic arts, Alphonse Mucha, and the French glass artist whose vision is forever etched on the most iconic of bottles, Émile Gallé.

To truly appreciate the art of Mucha and the design of the Perrier-Jouët Belle Epoque bottle, one must first understand the spirit of the Art Nouveau movement itself. Emerging in Europe around the 1890s, Art Nouveau was a deliberate and radical rebellion against the rigid, imitative historicism that had defined 19th-century design. In an age of increasing industrialization and mass production, a generation of artists and designers felt that the soul had been stripped from art.They rejected the straight lines and mechanical uniformity of the machine age and instead embraced the curvilinear, organic forms of the natural world. This new “modern style,” as it was known in Britain, or “Jugendstil” in Germany, found its visual language in the sinuous stalks of flowers, the tendrils of vines, the delicate wings of insects, and the graceful curve of a woman’s body. The guiding principle was the belief that art should not be confined to galleries and museums but should be integrated into daily life. From architecture and furniture to jewelry and posters, the goal was to elevate the decorative arts to the level of “fine art.”

It was into this vibrant Parisian landscape that Alphonse Mucha arrived. Born in a small town in Moravia, a region of the present-day Czech Republic, Mucha’s early life was marked by a deep connection to his Slavic heritage and a budding spiritual philosophy. He was a devout Catholic who believed that art had a moral purpose: to express beauty, which he defined as the “projection of moral harmonies on material and physical planes.” For Mucha, the artist’s mission was to “communicate with the soul of man” through a visual language that was both beautiful and spiritually uplifting. He disliked the term “Art Nouveau,” preferring to call his work “the Slavonic art,” a reflection of his belief that his style was a natural evolution of his native folk traditions.

Mucha’s artistic breakthrough came in 1894 when he was commissioned to create a poster for the legendary actress Sarah Bernhardt. His design for her play, Gismonda, was a sensation. It was unlike anything Parisians had seen before. Rather than the bold, garish colors of other posters, Mucha used delicate pastel shades and a vertical, elongated format. The figure of Bernhardt was depicted as a statuesque, goddess-like presence, surrounded by an ornate, halo-like mosaic and intricate floral patterns. The poster’s “whiplash curves” and sense of serene elegance captivated the public, and Bernhardt immediately signed Mucha to a six-year contract.

The success of the Bernhardt posters cemented Mucha as a master of the new style, and he quickly became one of the most sought-after commercial artists in the world. He applied his unique aesthetic to a vast array of products, from biscuits and cigarette papers to perfume and, most famously, champagne.

Mucha’s Champagne Posters: A Symphony of Elegance and Excess

Mucha’s work with champagne was a perfect marriage of art and commerce. The effervescence and celebratory nature of champagne, a drink synonymous with the Belle Époque, provided the ideal subject for his ornamental style. His most notable commissions came from the prestigious house of Moët & Chandon.

In 1899, Mucha was tasked with creating a series of posters for Moët & Chandon’s Imperial champagnes: ‘Dry Imperial,’ ‘Crémant Imperial,’ and ‘Grand Crémant Imperial.’ The designs were remarkably cohesive, featuring a single, elegant female figure in a flowing gown. In the posters, she appears almost as a priestess of a Dionysian cult, offering the viewer a glass of the divine nectar.

One of the most striking elements of these posters is Mucha’s mastery of detail and symbolism. The women are adorned with intricate jewelry and headpieces, their hair cascading in long, luxurious tendrils that mirror the floral motifs. The backgrounds are often a tapestry of rich colors and decorative patterns, a halo or a mosaic framing the central figure. In the Moët & Chandon Dry Imperial poster, a brunette woman with classical features wears an elaborate, high-necked dress, her gaze demure yet inviting. The poster for the White Star cuvée, in contrast, features a sensual, bare-shouldered blonde holding a bowl of grapes, her figure bathed in soft pinks and creams that subtly evoke the color of the champagne itself.

Mucha’s champagne posters were not just advertisements; they were works of art that transformed the product into something mythical and aspirational. They didn’t just sell champagne; they sold a lifestyle—one of beauty, luxury, and refined taste. Unlike the brightly colored, often chaotic posters of his contemporaries, Mucha’s designs were serene and harmonious. They were meant to draw the viewer in with their elegance and visual pleasure, making the act of consumption a beautiful, almost spiritual, experience.

He also created a famous poster for Champagne Ruinart in 1896, which similarly showcased his ability to transform an advertisement into a piece of fine art. Mucha’s genius lay in his ability to create a “visual language” that was both universal and deeply personal. He used the female form not just for decorative purposes but as a symbol of nature, beauty, and fertility, connecting the product back to its natural origins.

The Belle Époque Anemone: Gallé and Perrier-Jouët

While Mucha was revolutionizing the art of the poster, another master of the Art Nouveau movement was leaving his indelible mark on a different canvas: the champagne bottle. Émile Gallé, a renowned glass artist, ceramist, and furniture designer, was one of the most significant figures of the Art Nouveau movement in France. His work, deeply inspired by botany and Japanese art, was characterized by its delicate craftsmanship and elegant natural forms.

In 1902, the House of Perrier-Jouët commissioned Gallé to design a bottle for its prestige cuvée. The result was a design that would become one of the most recognizable and celebrated in the world of wine: a bottle adorned with a delicate spray of Japanese white anemones, their petals curving gracefully around the glass. Gallé’s design was a perfect expression of the Art Nouveau philosophy, a testament to the belief that beauty should be integrated into everyday objects.

However, the design was deemed too complex and expensive to produce at the time, and the four original magnum bottles were placed in the Perrier-Jouët cellars and largely forgotten. For more than six decades, Gallé’s masterpiece lay dormant, a hidden gem waiting to be rediscovered.

In 1964, the bottles were finally found by cellar master André Bavaret, and the House decided to release its 1964 vintage in Gallé’s breathtaking design. The world was reintroduced to a work of art that had been conceived 62 years earlier, and the Perrier-Jouët Belle Époque was born. This rediscovery was not just a commercial success; it was a powerful statement about the timelessness and enduring appeal of the Art Nouveau aesthetic. It was a fusion of exquisite art and an equally exquisite product, proving that the bottle could be as much a work of art as the champagne within.

The Unbroken Thread: From Mucha to Perrier-Jouët

The connection between Mucha and Perrier-Jouët is not direct, but it is profound and undeniable. It is a shared heritage rooted in the common philosophy of Art Nouveau. Both Mucha and Gallé saw their work as a way to create a dialogue between art, nature, and humanity.

- A Shared Philosophy of Nature and Beauty: Mucha’s posters, with their idealized women and floral halos, are a visual echo of Gallé’s anemone bottle. Both artists drew inspiration from nature, rejecting the artificiality of the industrial age. They elevated flowers, vines, and the human form to a state of almost mythical beauty, reminding their audiences of the fundamental connection between art and the natural world.

- The Pursuit of the Gesamtkunstwerk: Both Mucha and Gallé were proponents of the “total work of art.”Mucha designed not only posters but also calendars, menus, and even interiors, creating a unified aesthetic universe.Gallé, in his work, sought to unify form and function, believing that a beautiful bottle was not just a container but an integral part of the experience of enjoying the champagne. The very existence of the Maison Belle Époque in Épernay, Perrier-Jouët’s headquarters, which houses one of Europe’s largest private collections of French Art Nouveau, is a testament to the house’s deep and abiding commitment to this artistic ideal.

- Re-enchanting the Everyday: This core ethos of Art Nouveau is the final, and most crucial, link. For Richard Juhlin’s discerning audience at the Champagne Club, this is the ultimate takeaway. Mucha’s posters transformed a product advertisement into a moment of beauty on a city street. Gallé’s bottle turned an act of pouring champagne into an appreciation of a masterpiece. Both Mucha and Gallé understood that true luxury is not about excessive ornamentation but about the careful, artful application of beauty to enhance the small, precious moments of daily life.

In the end, Alphonse Mucha and Émile Gallé stand as two pillars of the Art Nouveau movement, one a master of the graphic arts, the other a virtuoso of glass. Their work for the world of champagne, from Mucha’s vibrant posters for Moët & Chandon to Gallé’s timeless design for Perrier-Jouët Belle Époque, is more than just a historical footnote. It is an enduring legacy that proves that when art and passion converge, they can create something truly magnificent, capable of captivating the senses and nourishing the soul, one perfect glass at a time.